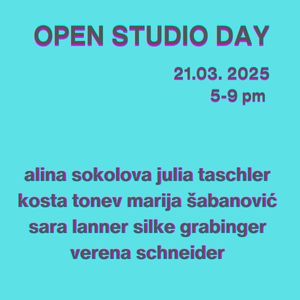

Since the beginning of March 2025, seven new artists have been settling into our creative space, bringing vibrant energy and new perspectives. Their artistic practices span across painting, sculpture, performance, new media, and choreography offering a diverse and engaging range of work. These Vienna-based emerging artists were selected through an open call held in late autumn 2024, and we cannot wait for you to discover the interesting projects they are working on!

Alina Sokolova

Alina Sokolova’s artistic practice can be described as an extensive exploration of movement. She is particularly interested in the repetitive gestures of contemporary labor and the mechanization of everyday life, which she primarily explores through painting. More info here.

Julia Taschler

In Julia Taschler’s work, she responds to regional culture, including food, folk tales, language, and the landscape, by combining jarring, surreal contrasts between her use of material and thematic choices. She studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in the class of Daniel Richter. More info here.

Kosta Tonev

In his practice, he explores the intersections of history and politics. He embraces a multidisciplinary approach, integrating performative and text-based practices across media such as drawing, video, installation, and sound. With humour and playfulness, Kosta Tonev offers a history of the present told in the first person. More info here.

Marija Šabanović

Marija Šabanović’s photographic work is often combined with narrative as a means of exploring themes such as the body, identity, social norms, and aesthetics of social classes. She has exhibited in group and solo exhibitions in Vienna, Thessaloniki, and Margate, and at festivals and institutions such as Foto Wien, Skin Festival, and Belvedere 21. More info here.

Sara Lanner

In her work Sara Lanner deals with topics of the body in relation to its context and the self as social choreography and sculpture. The ambivalences of interpersonal relationships and their points of contact, as well as our material and ecological realities, form the starting point for her artistic reflections. More info here.

Silke Grabinger

In her artworks and concepts, she combine contemporary dance with performative art and robotics, often in collaboration with AI. Her work focuses on critically examining social phenomena, artistic paradigms, and the role and position of the audience. More info here.

Verena Schneider

Verena Schneider is an interdisciplinary artist, dancer, handstand artist, and choreographer with a background in biology. She integrates movement disciplines into a sustainable performance practice rooted in contemporary dance, acrobatics, and hand balancing. Trained at FLIC Scuola di Circo and Le Lido, she has performed for choreographers like Bert Gstettner, Doris Uhlich, and Le GdRA. Co-founder of Kumquat and Vienna’s Freifall, she collaborates widely and received the 2024 DANCEWEB Scholarship. Currently pursuing an MA in Choreography, her research explores identity, the body’s ecology, and interdisciplinary performance. Her work has been shown internationally, including at WUK, WERK-X, and Centquatre Paris. More info here.